Latinos: Demographic Predominance Natalya Rahmann

David E. Hayes-Bautista graduated from UC

Berkeley and earned an MA and PhD in Medical Sociology at the University of

California Medical Center, San

Francisco. He is

currently Professor of Medicine and at the David

Geffen School

of Medicine at UCLA. Dr. Hayes-Bautista is Director of the Center for the Study

of Latino Health and Culture and researches the dynamics and processes of the

health of the Latino population in California.

From its colonial beginnings to its

modern day corporate success, California

has largely been influenced by Latinos. In La Nueva California: Latinos in

the Golden State, David E. Hayes-Baustista

examines the history of Latinos in California

and suggests that their future is brighter than expected. California¡¦s

first three spurts in population growth -the Gold Rush, railroad-facilitated

boom, and post-World War II baby boom- differed little from the rest of America.

However, the fourth demographic boom, occurring between 1975 and 1990, was

largely due to Latino immigration and births. Today, the Latino numbers ¡§surge

and resurge¡¨.1 Every year since 2001, over

half the state¡¦s babies are Latino. Though most consider population growth a

blessing, many Californians fear the Latino boom. Instead of enthusiasm, this

growth spurs resistance and apprehension. Far from welcoming the newborns and

newly arrived immigrants, some Californians support state-driven initiatives to

end affirmative action, limit immigration, end bilingual education, and keep

Latinos from becoming a majority. Many fear the changes in identity and society

in a California where half the

population is Latino. Since the beginning of the twentieth century, American

society has portrayed Latinos as a backward, impoverished underclass. A state

overrun by dysfunctional immigrants would mean a grim future for California,

but Hayes-Bautista opposes this portrayal of Latinos. He argues that Latinos do

not deserve the reputation they possess, and that Americans must accept the

Hispanic presence in order to create a cohesive, productive future for California.

Hayes-Bautista opens his book with

a history of Latinos in California

before their population boom. The first two chapters

cover California¡¦s beginnings up

until 1970. During this time period, Americans saw Latinos as dirty and

backward. Richard Henry Dana visited California

in 1835 and called the Californios ¡§an idle, thriftless people¡¨ comprised of

¡§hungry, drawling, lazy half-breeds¡¨ .2 Americans accepted Dana¡¦s

observations, and racism towards Latinos began. In 1870, whites prohibited

Latinos from holding political office, and Latinos gradually began leaving the

state. However, in 1910, the Mexican Revolution forced one-tenth of Mexican

citizens to flee to California.

Legal residential segregation forced immigrants into barrios, and Latinos began

to exist as a separate minority subculture. Willingness to take low-paying jobs

made immigrants tolerable to the whites, who viewed Latinos as cheap labor.

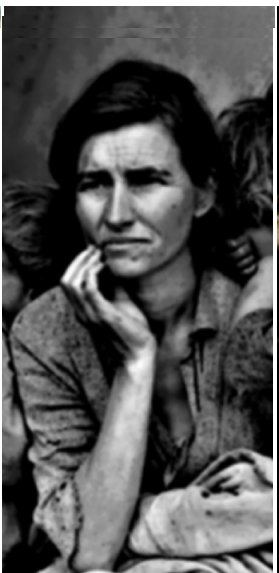

With the Great Depression, however, came anti-Latino rhetoric. Politicians

blamed Mexicans for unemployment, accusing them of stealing jobs from ¡§real¡¨

Americans. Suddenly anyone who ¡§looked Mexican¡¨, even a citizen, was liable to

be forcibly deported from their jobs. In Los Angeles

and San Francisco, immigration

agents held Latinos captive before transporting them to Mexico.

Deportation caused the number of Mexican immigrants in California

to fall from 199,165 in 1930 to 111,900 in 1940. The Zoot

Suit Riots in 1942 further tarnished Latino reputations and caused widespread

fear of this ¡§vagabond¡¨ race. Suddenly, all things Latino were considered

un-American and evil. Parents refused to teach their children Spanish and

encouraged them to embrace American culture. However, many children grew up

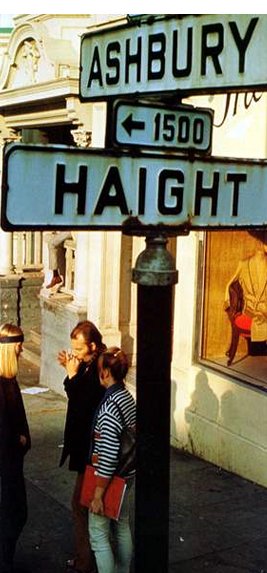

curious about their nationality. With the civil rights, anti-war, gay and

lesbian, and women¡¦s rights movements arrived the

Chicano movement. Chicanos were young revolutionaries, usually U.S.-born, who

rejected American culture in favor of Latino nationalism and Marxism. Though

¡§Chicano¡¨ is a derogatory term meaning juvenile delinquent, the young Latinos

embraced the name. Despite taking great pride in their nationality, less than

twenty percent of Latinos born in the U.S.

spoke Spanish and almost none had visited Mexico.

The Chicano movement included Cesar Chavez and the United Farm Workers,

numerous high school ¡§blowouts¡¨ in East LA, student

strikes, and the Brown Beret occupation of Catalina. Chicanos pushed for better

education, better healthcare, higher wages, more libraries, and greater

political involvement. Though the Chicano movement began to die in the early

1970¡¦s, it encouraged Latino involvement in higher education and new

immigration. By 1969, the American Association of Medical Colleges required

medical schools to admit significant numbers of Latino applicants. With the end

of temporary labor programs and national-origin quotas, California

once again became the perfect place for Latino immigration.

In the second section of his book,

Hayes Bautista describes the great wave of Latino immigration between 1970 and

1990 and its effects on California.

When the bracero program ended, the Mexican guest

workers returned to their American jobs, but now returned as immigrants with

families. Along with the laborers came foreign-educated Latino doctors, who

served the Hispanic population and formed the California Hispanic American

Medical Association. Despite the small handful of white-collar professionals,

most immigrants were poor and uneducated, bringing new social problems. Because

minorities tended to have higher poverty levels, discussion of poverty now

meant discussion of minority issues. President Johnson committed himself to

ending poverty, but in the process portrayed Latinos as a permanent underclass.

With the lowest percentage of high school graduates and lowest average

household income, Latinos threatened to corrupt California.

Many whites feared that easy access to welfare and benefits would discourage

the foreigners from working. However, between 1940 and 1980, Hispanic males had

the highest labor force participation, lowest percentage of welfare users, and

highest percentage of nuclear families out of all minority groups. Despite

this, Latinos remained the poorest minority, earning a less than their Asian,

African-American, and Native American counterparts. The poverty level fell,

however, as Latinos achieved higher education. When the Hispanic population

boom saved the University of California

from closing a campus, Latinos received new opportunities for education.

President Nixon noticed the potential of minority groups and implemented

affirmative action. Immigrants rejected American restrictions, and ¡§Latinos

began to define Latinos¡¨.3 Latinos spoke Spanish, introduced

contemporary Latin American culture, and influenced the food industry and

corporate world. As the immigrant presence increased from twenty percent in

1960 to fifty percent in 1990, Spanish became the preferred language of half

the Hispanic population. By 1990, the most popular newspapers, TV shows, and

radio stations in California had

Spanish editions. Since Latinos typically spent eighteen percent more than

non-Hispanics when buying food, the food industry began to cater to the Latino

market, reaping huge rewards. By 1993, salsa outsold catsup and tortillas

outsold white bread. Executives realized that marketing to Latinos would mean

future success in California, and

the Latin Business Association began to make great achievements. The Latino

population boom changed Latinos from an unwanted minority to a valuable

American sub-culture.

The book¡¦s third section covers the

Proposition 187 crisis and ensuing events during the years 1990-2004. Immigrant

Latinos moved into deserted ghettoes, restored them, and brought Southern

California¡¦s cities back from the brink of social and economic

death. However, the 1992 riot in Los Angeles

soon rekindled widespread fear of Latinos, especially illegal immigrants. Many

Americans blamed illegal aliens for all social problems, and anti-Latino rhetoric

once again became the norm. The media blamed Latinos for crime and low school

rankings. Some Americans even accused immigrants of spying, claiming that they

could not be loyal to both their homelands and the United

States. Governor Wilson¡¦s tagline ¡§Our

Borders are Out of Control¡¨ claimed that between two and five thousand illegal

immigrants snuck across the border every night. Soon afterward Proposition 187

ended affirmative action and bilingual education. The ¡§Civil Rights Initiative¡¨

forbade the state from providing an advantage due to race, ethnicity, or

gender. Countless attacks destroyed Latino pride, and Latinos began to leave

the state. A widespread message that presented a positive Latino image was

needed. The answer came in the form of the Maldef

Public Announcement, a TV commercial that portrayed Latinos as normal,

middle-class, patriotic Americans. Latinos appreciated the realistic

commercial, while many whites felt ¡§the commercial contradicted what they knew

about Latinos¡¨.4 Though they noticed the

Latino work ethic, they felt that since few Latinos achieved success even

though the U.S.

offered opportunities to all, Latinos could not be true Americans. However,

statistical evidence proved that most immigrants move up the socioeconomic

ladder: after twenty five years in America,

eighty percent lived above the poverty level. As time went by, more Latinos

joined the middle class and gained a more important role in American society.

In his fourth section,

Hayes-Bautista evaluates the past of Latinos in California

and makes predictions for the future. Instead of making the state un-American,

Latinos give California a ¡§new

regional identity¡¨.5 The large population

of Latinos creates a self-sustaining economic base and distinctive culture. By

2040, California will be

forty-eight percent Latino, creating the first Hispanic majority in the United

States. This majority may mean either

prosperity or doom, depending on the strength of California¡¦s

economy after years of intensive policy work and public investment. The high

average Latino life expectancy may help the state¡¦s overall health, and

education in Californian history may aid the formation of civil society.

However, a greater concentration of Latinos may lead to riots and violence,

with under-funded and underperforming public schools. If few Latinos go on to

medical school, there may not be enough physicians to sustain the exploding

population. At the present, Latino education is in jeopardy. Latinos have never

been proportionately represented by the University

of California¡¦s student body, and

every year fewer Latinos attend college. The reason Latinos do not reach their

educational potential is because they do not start with parental advantages.

After 2010, baby boomers will leave the workforce and workers will increasingly

be Latino. The key to whether California¡¦s

future is prosperous or bleak lies in the level of Latino educational

attainment.

Hayes-Bautista writes his book to

educate Californians about a minority that will soon become a majority. This

demographic boom will redefine California¡¦s

identity. Because the media often portrays Latinos in a negative light, a book

of this nature is necessary to end the current prejudice and prepare

Californians for the future. Some Californians do not know the struggles their

Latinos neighbors experience and hope the ¡§Mexican problem¡¨ will go away. With

immigration and the Latino population¡¦s high growth rate, however, there is no

chance of Latinos ¡§becoming extinct¡¨.6 Instead of rejecting Latinos,

Californians must embrace them. Whites and other minorities will soon be

outnumbered. In order to survive in a Latino-dominated state, non-Hispanics

must understand Hispanic realities.

As Director of the Center for the

Study of Latino Health and Culture, a resident of California,

and a Latino himself, Hayes-Bautista is a reliable source on his subject. His

job as a professor in medicine at UCLA helps him experience firsthand the

present level of education of Latinos and the status of Latino healthcare.

Hayes-Bautista believes that in order to understand the future, we must

understand the past. Californians cannot handle a state that is half Latino if

they do not understand the history of their neighbors and the surprisingly

similar traits they share. He emphasizes the importance of ¡§a well educated

workforce¡¨ and frequently repeats that only through education can Latinos

escape poverty and compete with whites for the jobs and status they deserve.7

Most importantly, Hayes-Bautista feels that Latinos

embody the American Dream and are no different from other Americans. Their work

ethic and commitment despite poverty represent the core American values: hard

work and dedication. Time and work will bring Latinos out of poverty and into

mainstream American society, although many Latinos have already achieved middle

class status. As the ethnic character of California

develops, the state will either promote a ¡§culturally dynamic society¡¨ or a

society where ¡§ethnic groups are at war with each other¡¨ (12). Frequent usage

of statistics, data, and graphs support Hayes-Bautista¡¦s views and show the

validity of his statements. An objective viewpoint saves him from letting his

own opinions get in the way of historical fact, adding to the reliability of

his statements and arguments.

Critics say that the main

weaknesses of the book lie in its outdated sources and its ignorance of many

aspects of Mexican immigration. Most of the books Hayes-Bautista cites are at

least thirty years old, making the book feel ¡§stuck in

the 1970¡¦s¡¨.8 The lack of a current historical narrative makes the

reader question the reliability of the sections that involve more recent

events. Reviewer Gilbert Gonzalez points out the books greatest flaw: a

complete ignorance of ¡§free trade¡¨ and Mexican migration, including the North

American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA). Destroying the Mexican economy, NAFTA

lowers import barriers to U.S.

agricultural products, forcing Mexican farmers into bankruptcy. In the future,

NAFTA may force thousands of bankrupt farmers to flee to California.

Although free trade heavily impacts Latino society, Hayes-Bautista disregards

the topic entirely. Nonetheless, most critics feel that despite small weakness,

Hayes-Bautista presents a strong work.

Even so, Hayes-Bautista tends to

repeat his statistics, making certain aspects of the book extremely monotonous.

However, this frequent use of statistics also adds to the believability of his

statements. The wide range of issues covered help readers to understand Latinos

and better prepare for the future ahead. Furthermore, an optimistic tone

¡§inspires confidence in the future of American identity¡¨.9 A

synopsis of events from California¡¦s beginnings through 2040 makes the work

feel complete, and the analysis and commentary show the author¡¦s great passion

for the subject. A bit of repetition does little to detract from the admirable

book.

During the twentieth century, California

grew from a reflection of standard American society to a state with a culture

and people of its own. During the first three non-Latino population booms, California

was ¡§not unlike the rest of America¡¨,

only ¡§a bit ahead of the trends¡¨.10 Californians accepted the racist

definitions of Latino and hoped that the ¡§Mexican problem¡¨ would go away.

Atlantic Americans killed early Latino influence in California,

and, after Dana¡¦s widely published warning against the savages of the West,

portrayed Latinos as violent troublemakers. Ignoring their southern neighbors,

Californians accepted Atlantic inventions and ideas, such as automobiles and

white supremacy. However, the growing Latino presence in California

set it apart from the rest of the country. Diversity in California

made it different from the all-white regions of the United

States. Latinos soon became a valuable

market and changed the faces of the Californian food industry, business world,

and corporate world forever. More Californians became bilingual, and the

popularity of Latin American pop culture differed from the conservative Anglo

sections of the rest of the country. Eventually, the presence of Latinos would

become the very essence of California¡¦s

identity.

One of the largest, most diverse,

and most Latino states, California

can be seen as a model of commercial, economic, and social success for the rest

of the country. Rags to riches stories of immigrants can rekindle faith in the

American Dream. Most importantly, California

will show that a state of Latinos can be successful. Americans consider Latinos

backward, but Hayes-Bautista realizes their potential. A state where ¡§diversity

is approached from a Quaker-like stance¡¨ will be examples for the nation.11

Americans consider California the

picture of beauty and success. California

is the land of opportunity, for Americans and for Latino immigrants. The future

of Latinos in California will

show the country the state¡¦s tolerance, perseverance, and success.

Hayes-Bautista presents a

relevant issue in his book. Educating people about the past to prepare for the

future, Hayes-Bautista has created an informative historical work. Presenting

Latinos as a misunderstood minority, Hayes-Bautista encourages Californians to

¡§make [their] own history¡¨ and accept Latinos.12 Bursting with

statistics, analysis, and optimistic hope, La Nueva California: Latinos in

the Golden State is an excellent representation of Latinos and the future

of California.

1. Hayes-Bautista, David. La Nueva California:

Latinos in the Golden State.

Los Angeles: University

of California Press, 2004 1.

2. Hayes-Bautista, David 16.

3. Hayes-Bautista, David 89.

4. Hayes-Bautista, David160.

5. Hayes-Bautista, David 207.

6. Hayes-Bautista, David 37.

7. Hayes-Bautista, David 228.

8. ¡§La Nueva California-Latinos in the Golden

State.¡¨ Book In Print.com 01 June 2005. 01 June 2005 <http://www.booksinprint.com/merge_shared/detao;s.asp?item_uid=

57065725& viewItemIndex=0&n>.

9. Gonzalez, Gilbert. ¡§La Nueva California:

Latinos in the Golden State.

(Book Review).¡¨ High Beam Research 22 March 2005. 01 June 2008 <http://www.highbeam.com/DocPrint.aspx?DocId=

1G1:138313160>.

10. Hayes-Bautista, David 1.

11. Hayes-Bautista, David 228.

12. Hayes-Bautista, David 226.